Business

Blog post

Humankind has used aluminium in one way or another as far back as ancient times, when the Greeks and Romans employed alum, an aluminium-based salt, for such things as tanning hides, dressing wounds, and fireproofing wood fortifications. But even though aluminium is the earth’s third most abundant element, it took us centuries to come up with an inexpensive way to separate the pure metal from the compounds in which it naturally occurs.As a result, throughout much of history, aluminium was considered a precious metal. One account says that Emperor Napoleon III threw a banquet where the most honored guests were given aluminium cutlery, while everyone else had to make do with gold.

Industrial at last

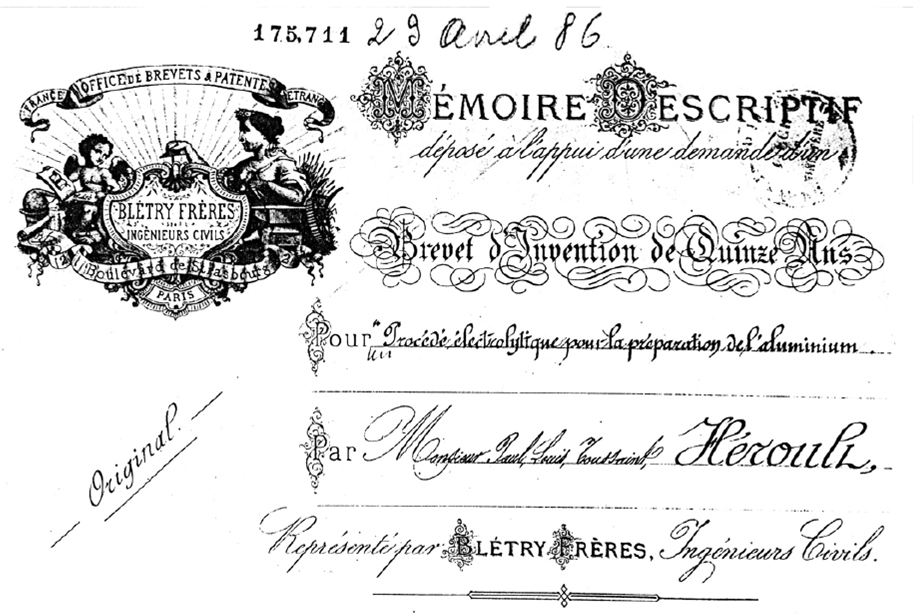

The breakthrough in refining aluminium came about in 1886, when two 22-year-old inventors working separately, on different continents—Charles Hall in the U.S., and Paul Héroult in France—figured out how to inexpensively extract aluminium from aluminium oxide (alumina) by using electrolysis. The two battled over patents for years, but ultimately became friends. The Hall-Héroult process was named for both of them, and is still in use today. And thus the era of industrial aluminium was born. Since 1886, one billion metric tons of the metal have been produced, of which 75% is still with us today. In 1888, the Austrian chemist Karl Josef Bayer patented an inexpensive chemical process to extract alumina from bauxite, another process that is still in use.

Aluminium takes off

Aluminium’s intrinsic properties—light, strong, corrosion resistant, conductive—immediately made it popular for a huge variety of applications. In the early 20th century, it was used for such things as power lines, elevated train wiring, cooking pots and pans, and aluminium foil, which came onto the market in 1910. The development of alloys improved the metal’s physical properties and led to other new fields. With its combination of strength and light weight, aluminium helped man to fly. In 1903, the American aircraft pioneers Wilbur and Orville Wright used aluminium parts to make a lightweight engine for their Flyer-1, the first controlled aerial vehicle in history, which Orville piloted for 12 seconds. Aluminium was a vital material during WWII, used for aircraft frames, ship infrastructure, radar chaff, and mess kits. American families were encouraged to turn in the foil from their gum wrappers and cigarette packs, to be recycled for the war effort. “Tin foil drives” offered free movie tickets in exchange for aluminium foil balls.

Cans and shuttles

A milestone in recycling occurred in 1959, when Coors Brewing Co. pioneered the all-aluminium two-piece can, replacing the tin-lined steel container that was then the industry standard. Aluminium was lighter, made beer chill faster, and didn’t alter its taste. But best of all, Coors promised customers to buy back the cans for a penny apiece and recycle them. Coca-Cola and Pepsi followed by packaging their drinks in aluminium cans, starting in 1967. As Jules Verne foretold in the 1865 novel From the Earth to the Moon, aluminium would be a crucial element of the Space Age. The Apollo Command Module was made of an aluminum honeycomb sandwiched between sheets of aluminum alloy. Sputnik, the world’s first artificial satellite, was a metal sphere made from an aluminium alloy. In the 1980s, aluminium oxide rocket boosters were used to launch space shuttles. Constellium’s Airware® technology was part of the first successful first flight test of NASA’s new Orion spacecraft, built to take astronauts into deep space.

Cars and computers

Aluminium’s properties have made it ideal for everything from commercial jets to cell phones. Eighty-five years after the Wright brothers used aluminium in their Flyer-1, Boeing built its 747-400 jumbo jet with more than 66,000 kg of the material. In 2015, the automaker Ford skimmed 315 kg off its F-150 truck by building it with an all-aluminium body, a revolution for light-duty pickups. In the consumer electronics sector, Steve Jobs took advantage of the aesthetic possibilities of aluminium, making it a staple in Apple’s sleek, lightweight laptops, iPads, and iPhones. In fact, Jobs was such a fan of the material, he commissioned a custom yacht made from it.

History on display

Paris, France, is home to the only resource center in the world dedicated to aluminium, the nonprofit Institute for the History of Aluminium (Institut pour l'histoire de l'aluminium), founded in 1986. The center fosters study of the metal’s technical, economic, industrial, commercial, and cultural history. It also serves as a repository for historical equipment and products, displaying the amazing variety of uses for this material, from 19th-century binoculars to a 1966 aluminium dress by Paco Rabanne, as well as a collection of rare automobiles by Jean-Albert Grégoire.

With worldwide consumption of aluminium expected to exceed 80 million metric tons by 2023, this magnificent metal’s future should continue to glitter as brightly as its past.

First aluminium patent dated April 1886